Behind the Stone Walls: A Not-So-Stuffy Look at Ontario’s Historic Gaols and Courthouses

If you’ve ever wandered through an old Ontario town and spotted a sandstone building with tiny windows and iron bars, you might have wondered: What stories live behind those walls? The answer: plenty. Some tragic, some surprising, some downright bizarre, and all part of the story of how Ontario kept the peace, tried its criminals, and occasionally locked up the wrong people.

Ontario’s early jails and courthouses, often called gaols (pronounced “jails”), were more than places of judgment and punishment. They were community hubs, political battlegrounds, and sometimes accidental social clubs where the sheriff, the judge, the accused, and the town gossip all crossed paths. Today, many survive as museums, archives, event venues, or architectural landmarks. But their past lives? Well… let’s lift the iron latch and step inside.

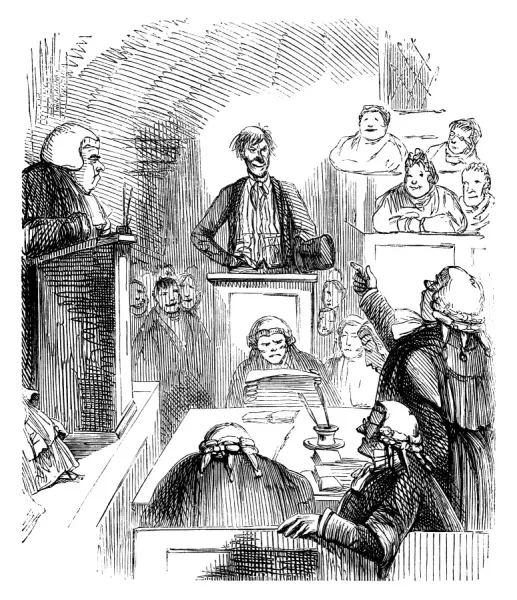

NOTE: Some images are illustrations or reconstructions used to represent early courtrooms and gaols where photography did not yet exist.

A typical 19th-century Ontario stone gaol, built to intimidate, contain, and remind communities that law and order had arrived.

The Early Days: Courts on the Frontier

Back in the late 1700s and early 1800s, Ontario, then Upper Canada, was a frontier dotted with log cabins, muddy roads, and the occasional tavern that doubled as a community hall. Law and order existed, but not always in convenient locations. Early courts often met in homes, inns, barns, and sometimes outdoors when the weather cooperated.

The very first criminal courts operated under British law, and traveling judges, known as “circuit judges”, rode from settlement to settlement on horseback. Imagine being accused of theft and having to wait weeks for the judge to arrive, only to be tried in a tavern kitchen between the dinner service and someone playing a spirited fiddle in the corner.

Proper courthouses and gaols followed soon after, but “proper” is generous. Early gaols were often wooden, drafty, and laughably insecure. It wasn’t uncommon for prisoners to dig their way out, squeeze between beams, or simply walk away when the lone constable wasn’t paying attention.

Communities learned quickly: stone was better than wood… and thicker stone was better still.

A reconstruction of an early colonial courtroom, where justice in Upper Canada was often delivered in modest, multi-purpose spaces.

Stone Walls and Iron Discipline: The First Real Gaols

By the mid-1800s, Ontario began building sturdier stone gaols, handsome structures that blended Georgian or Victorian architecture with a healthy dash of intimidation. Many included:

- high exterior walls

- barred basement cells

- a central gallows yard

- sheriff’s residence attached to the front (because apparently living beside criminals was a perk)

These gaols became symbols of civic pride. A town with a courthouse and gaol wasn’t just a settlement, it was a centre of governance.

Some well-known early examples include:

The Old Cobourg Jail (Northumberland County Gaol)

Built in 1857, this impressive limestone fortress has seen everything: debtors, murderers, political agitators, and even a few unlucky souls headed to the gallows. The sheriff’s family lived upstairs, imagine the kids tossing a ball around while prisoners shouted from below.

Cobourg’s Old Gaol, completed in 1857, served as both jail and sheriff’s residence — blending domestic life with incarceration.

The Goderich Gaol (Huron Historic Gaol)

One of Ontario’s most unique jails, built in 1841 as an octagonal structure. This architectural oddity was designed so the keeper could stand in the centre and observe every cell at once, an early “panopticon” idea. It now operates as a fascinating museum, complete with stories that are equally fascinating.

The octagonal Huron Historic Gaol in Goderich was designed so a single keeper could observe every cell at once.

The Thunder Bay (Original Port Arthur) Courthouse

Long considered one of Ontario’s most beautiful courthouses, this grand 1920s building features a stone façade, massive columns, and a courtroom that looks straight out of a classic courtroom drama.

These jails weren’t just places to hold someone overnight for stealing a chicken. They were the backbone of early justice, messy, imperfect, and very human.

Thunder Bay’s Port Arthur Courthouse reflects the evolution from frontier justice to grand civic institutions in Ontario.

What Landed People in Gaol? (Spoiler: Pretty Much Anything)

If you think the criminal code today is complicated, take a peek at 19th-century justice. You could be jailed for:

- public drunkenness

- swearing

- vagrancy

- “stubbornness” (yes, really)

- debt

- working on a Sunday

- stealing livestock

- insulting a magistrate

- being “of ill fame” (whatever the sheriff decided that meant…)

Of course, serious crimes also filled the cells, but many prisoners were ordinary people who simply ran afoul of social rules or couldn’t pay a fine.

Conditions were rough. Straw bedding, iron bars, little heat in winter, questionable sanitation, and meals that occasionally resembled punishment more than sustenance. Yet, many prisoners described boredom as the worst torture. Days were long, monotonous, and spent in tiny spaces.

A small-town rural gaol typical of 19th-century Ontario, often under-heated, overcrowded, and built more for containment than comfort.

Executions: Public Spectacles Nobody Liked but Everyone Attended

Before Canada abolished capital punishment, gaols were also places of execution. In smaller towns, these events drew large crowds, morbidly curious, somber, or sometimes disturbingly enthusiastic.

The Huron Gaol in Goderich conducted several notorious hangings, including the haunting case of Nicholas Meloche in 1861, whose crime of murder shocked the community. The execution attracted thousands, many traveling long distances just to witness the grim spectacle.

By the late 1800s, executions moved behind high walls, but the fascination never disappeared.

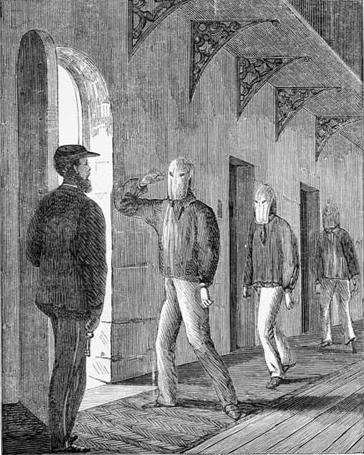

An illustration representing a 19th-century gaol inmate — many were imprisoned for minor offences or unpaid debts.

Famous Trials: Courtrooms Full of Drama

Ontario’s historical courts were never dull. Judges, sheriffs, lawyers, and everyday citizens created moments that would rival today’s courtroom TV dramas.

The Donnelly Trials (Lucan, Ontario)

Perhaps the most famous rural Ontario tragedy, the Donnelly family feud culminated in 1880 with a murderous midnight attack. Numerous trials followed, packed with testimony, scandal, fear, and whispered conspiracies. Despite widespread belief that justice was not served, no one was convicted. The Donnelly saga remains one of the province’s most debated criminal stories.

An illustration representing a 19th-century gaol inmate — many were imprisoned for minor offences or unpaid debts.

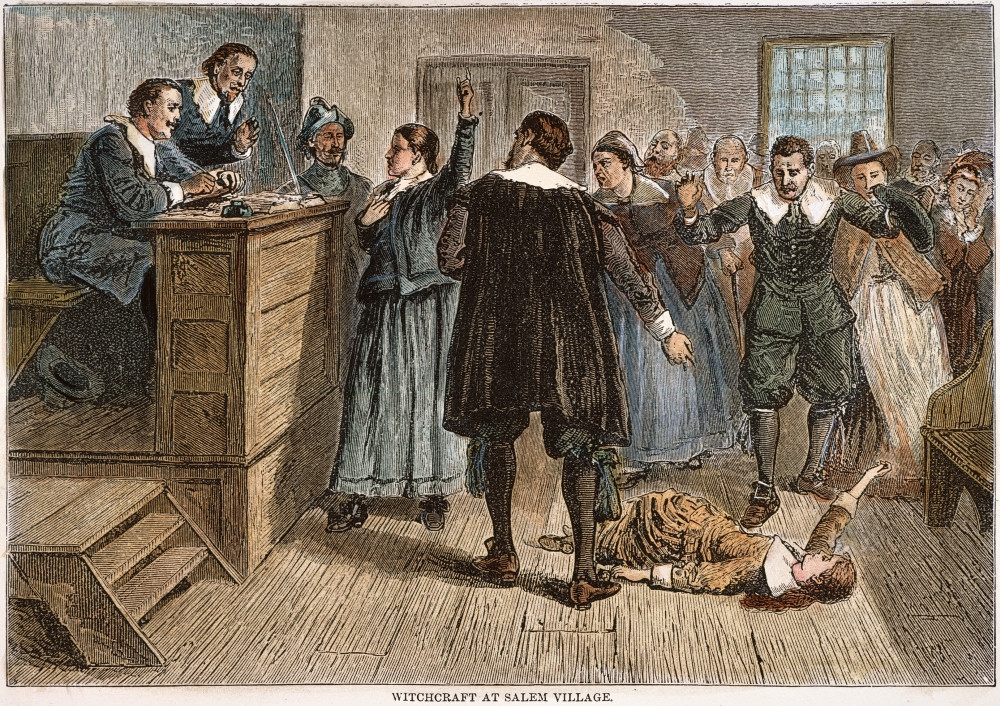

The Cornwall Witchcraft Case (Yes, Witchcraft!)

In 1893, a woman named Catherine Winters of Cornwall was charged with “pretending to practise witchcraft,” a law imported from medieval England. Her crime? Fortune telling. The trial made headlines and showcased just how unusual old laws could be.

A period illustration reflecting courtroom proceedings of the late 1800s, when outdated laws like witchcraft charges still existed.

Cobourg’s Famous Forgery Case

Cobourg’s courthouse witnessed a sensational 1860s trial involving an English nobleman accused of forging documents to claim a false inheritance. The courtroom overflowed with spectators eager to hear the shocking details. Newspapers across the continent reported on the scandal.

Victorian courtrooms often overflowed during sensational trials, turning legal proceedings into public spectacles.

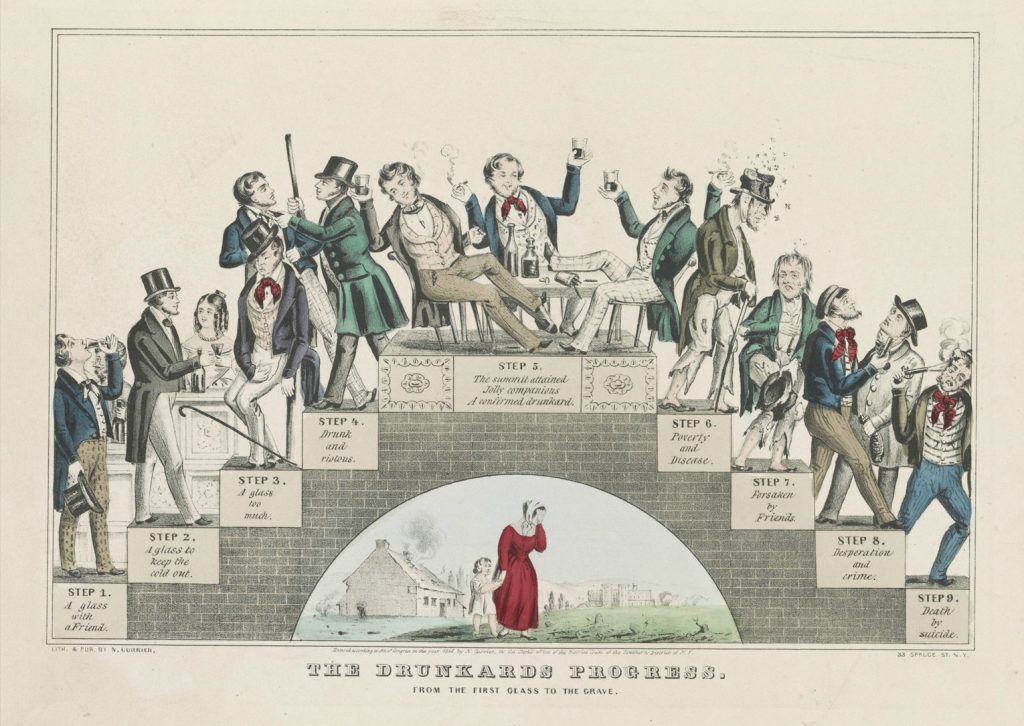

The “Whiskey Insurrection” Trials

Post-Confederation Ontario had several alcohol-related riots, often sparked by new temperance laws. In one southwestern Ontario case, dozens were arrested after a tavern brawl grew into a small riot. Their trials, complete with fist-shaking speeches and colourful characters, are still referenced in local museum tours.

Temperance-era unrest led to numerous alcohol-related trials, filling Ontario courtrooms with fiery debate and colourful characters.

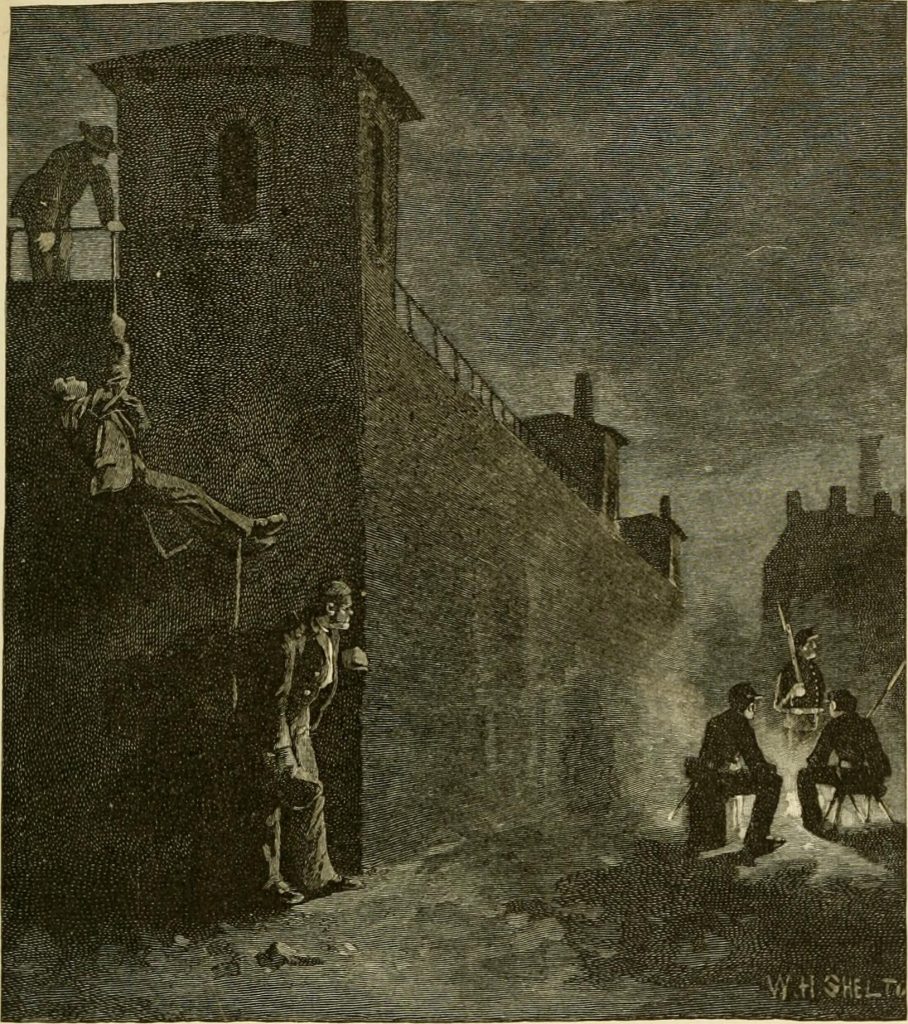

Jailbreaks! (Because Stone Walls Aren’t Everything)

Ontario’s early gaols saw more than a few escapes, some clever, some ridiculous:

- One prisoner in the old Kingston area gaol dug through mortar with a spoon.

- Another convinced the guard to let him out “just for a minute” and disappeared into nearby woods.

- A pair of Northumberland prisoners used a smuggled saw to cut through bars, only to get caught when the sheriff noticed the sawdust.

- In Goderich, several prisoners escaped by prying loose a section of the octagonal wall. Legend says the jail keeper was so embarrassed he refused to discuss it for years.

Escapes often turned these jails into places of folklore—and sometimes comedy.

Historic illustration of a prisoner escaping from a 19th-century Canadian gaol.

Famous or Notorious Prisoners

Some inmates gained fame simply by being unusual:

The Gentleman Thief

A well-dressed, articulate man held in the Cobourg gaol during the 1870s charmed the sheriff’s family, read poetry, and entertained other inmates before disappearing after release and never being heard from again.

Inside a 19th-century Ontario gaol, thick stone walls, iron doors, and narrow cells reveal the harsh realities of early incarceration.

The Bell-Stealing Tourist

In the 1880s, a visiting American was jailed overnight for attempting to “borrow” a church bell clapper as a souvenir, much to the outrage (and amusement) of the town.

Illustration representing a 19th-century gaol inmate — a reminder that not all jail stories were grim. Some, like the infamous “bell-stealing tourist,” were simply bizarre.

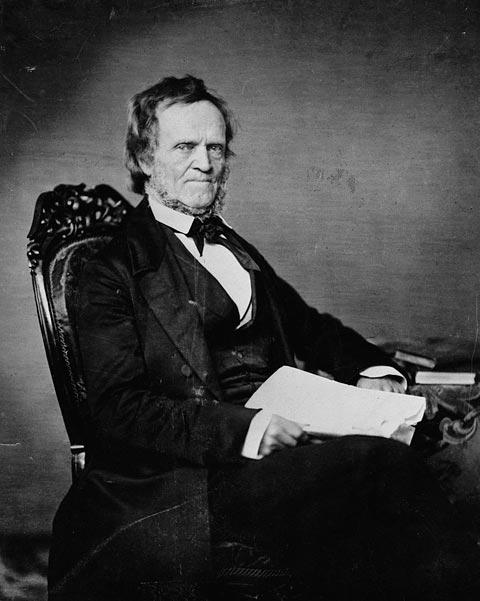

Political Prisoners of the 1837 Rebellion

During the Upper Canada Rebellion, several political agitators, including supporters of William Lyon Mackenzie, were held in local gaols. Their stories became symbols of political reform and sparked decades of debate over justice and loyalty.

Supporters of William Lyon Mackenzie and other reformers were held in local gaols during the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837, turning jails into symbols of political struggle.

Why These Buildings Matter Today

Many of Ontario’s historic gaols and courthouses have survived, and thank goodness. They serve as:

- museums

- archives

- cultural centres

- tourist attractions

- film locations

- architectural treasures

They remind us that justice is always evolving. Laws change, values shift, and what once seemed normal (jailing someone for swearing!) now seems absurd.

More importantly, they preserve the human stories, those of the accused, the innocent, the guilty, the reformers, the officers, and the communities who lived through times very different from today.

Walking through one of these old gaols today, you can almost hear the echoes: the clank of iron keys, the footsteps of a sheriff on night patrol, the murmurs of prisoners, and the hum of courtroom spectators waiting for a verdict.

Many former Ontario gaols now operate as museums, preserving original cells, iron doors, and the stories of those once held inside.

A Few Ontario Historic Gaols and Courthouses to Visit Today

These sites offer tours, artifacts, and storytelling that bring the past to life:

Huron Historic Gaol (Goderich)

A National Historic Site with preserved cells, keeper’s quarters, and an eerie gallows yard.

The Huron Historic Gaol in Goderich is one of Ontario’s most distinctive jails, known for its octagonal design, preserved cells, and haunting gallows yard.

Cobourg’s Old Gaol (Northumberland County)

Architecturally stunning, with deep local history, old cells, and chilling stories.

Built in 1857, Cobourg’s Old Gaol once housed prisoners, debtors, and the sheriff’s family — all under the same limestone roof.

Brockville Court House

A spectacular 1809 Neoclassical structure that still operates as a courthouse, one of the oldest in Ontario.

Completed in 1809, the Brockville Court House remains one of Ontario’s oldest functioning courthouses and a landmark of early justice.

Thunder Bay (Port Arthur) Courthouse

An architectural masterpiece from the 1920s.

The Port Arthur Courthouse in Thunder Bay reflects the shift from frontier justice to grand civic institutions in early 20th-century Ontario.

Perth’s 1843 Court House and Gaol

One of the most charming early judicial complexes, surrounded by heritage buildings.

Perth’s 1843 Court House and Gaol form one of Ontario’s most charming early judicial complexes, still anchoring the town’s heritage streetscape.

Many towns also offer “ghost tours” or “crime walks,” adding a little theatrical flair to their justice-filled pasts.

Final Thoughts: Stories Behind the Bars

Ontario’s historic jails and courthouses are more than stone, iron, and wood. They are snapshots of who we were, and stepping stones to who we became.

They remind us that justice is an ongoing conversation. And they prove that even the most intimidating buildings contain not just records, but real human drama: scandals, triumphs, tragedies, absurdities, and moments that still make us shake our heads.

So, the next time you stroll past one of these grand old structures, pause for a moment. Behind those walls lived stories, messy, fascinating, unforgettable stories that shaped Ontario in ways no textbook ever could.

And if you happen to hear a faint echo of footsteps or the whisper of a long-forgotten tale… well, that’s just history saying hello.

The Goderich Courthouse stands as a companion to the nearby gaol, symbolizing the balance between judgment, punishment, and civic order.