Agricultural Fairs in Ontario: Heritage on Display, Community in Motion

Walk through any Ontario fairground in September and you’ll smell it before you see it, fresh-cut hay, cider doughnuts, diesel from a tractor-pull, and that unmistakable barn-sweet scent of shavings and show cattle. Agricultural fairs feel timeless because, in Ontario, they almost are. They predate our cities’ skylines, outlasted wars and recessions, and still carry a simple promise: bring people together around food, farming, and friendly competition.

This article traces how fairs began here, why they matter now more than ever, how locals can support them, and what’s behind the recent friction with some municipal councils over rules, fees, and funding.

Fairground

How Ontario’s fairs began

Agricultural fairs arrived with British colonial practice: organized shows where farmers compared stock and seed, swapped knowledge, sold goods, and received prizes to spur improvement. Ontario’s fair tradition is tied to the rise of agricultural societies, community organizations devoted to “improving” agriculture through premiums, demonstrations, and education.

- 1792: The first agricultural society in what is now Ontario formed at Niagara-on-the-Lake (then Newark). Its activities included annual fairs and exhibitions—an early blueprint for what followed across Upper Canada.

- Early 1800s: Local fairs multiplied under township and county societies. One of the best-documented survivors is the Williamstown Fair in Glengarry; Ontario’s heritage plaque records a patent granted in 1808 and land set aside in 1814 “for the express purpose of holding a fair.” It proudly styles itself Canada’s oldest annually held fair.

- 1840s–1870s: Upper Canada (later Ontario) experimented with a provincial agricultural fair that rotated among host towns. That series, organized by the Provincial Agricultural Association and Board of Agriculture, ran from 1846 and ultimately seeded the idea for larger, more permanent exhibitions. Toronto’s Toronto Industrial Exhibition launched in 1879 and evolved into today’s Canadian National Exhibition (CNE), an urban cousin whose roots are unmistakably agrarian.

By the late 19th century, fairs had become a civic rhythm, supported by volunteer-run agricultural societies and coordinated provincially. Today, societies operate under Ontario’s Agricultural and Horticultural Organizations Act, which sets basic governance rules and reporting obligations to the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs.

The Ontario Association of Agricultural Societies (OAAS) provides training, judging standards, and a network that keeps hundreds of fairs consistent and resilient, an institutional backbone to a very local tradition.

Old Fair

What fairs do for communities (it’s more than cotton candy)

They keep agriculture visible. When a child watches a 4-H member brush a heifer, or when a baker’s pie wins a ribbon next to heritage wheat sheaves, the food system snaps into focus. Fairs remain one of the few places where urban and rural neighbours meet as producers and eaters, not just shoppers and clerks.

They move money locally. Admissions, vendor stalls, entertainment bookings, and concession contracts circulate through nearby main streets. Many fairgrounds double as year-round event sites, home to markets, service-club fundraisers, festivals, and emergency staging areas, so the asset works beyond “fair week.”

They train volunteers and leaders. Fairs are laboratories for community leadership: budgets, sponsorships, safety planning, logistics, and governance. OAAS’s leadership and board-development resources exist because societies are major volunteer institutions, often second only to minor sports in their ability to mobilize people.

They conserve rural heritage—while staying current. Yes, you’ll find threshers and draft-horse hitches. You’ll also find drone demos, soil-health talks, and food entrepreneurship showcases. The formula, competition, exhibition, and celebration, adapts readily to new crops, cuisines, and technologies.

Volunteer Training

How locals can support their fairs (beyond buying a ticket)

1) Volunteer where it actually hurts. Every fair has two or three perennial gaps, parking marshals, data counters, overnight barn monitors, post-event teardown. Ask the secretary, “What’s the hardest job to fill?” Then fill it. Leaders are made in the unglamorous shifts.

2) Sponsor strategically. Small, repeated gifts often beat one-off cheques. Cover the ribbons for the junior baking classes. Buy wheelbarrows for the show barn. Fund a safety upgrade. Tangible, visible support becomes part of the fair’s story and lowers costs in future years.

3) Tell the data story. Help the society count visitors, map postal codes, and summarize exhibitor numbers. Clean facts, “X visitors; Y postal codes; Z classes entered”, are gold when councils debate fee waivers or in-kind services. (Under the Act, societies already file annual returns; local stats make that picture clearer for municipalities.)

4) Build bridges to year-round partners. Connect your fair with the farmers’ market, BIA, service clubs, libraries, and schools. Cross-promotions (recipe contests at the market; ag-literacy kits at the library; a school art wall in the display hall) extend the fair’s reach and justify municipal support as “economic development,” not just “entertainment.”

5) Show up at budget time. Be the friendly face in the council chamber who can explain how a modest grant or a waived road-closure fee multiplies into vendor sales and foot traffic downtown.

Sponsor Signs

Why some councils are pulling back (and what they’re weighing)

Most municipal councillors aren’t anti-fair. They’re juggling limited budgets, liability, and competing policy goals. Four forces drive the current friction:

1) Standardized fees and cost recovery.

Under Ontario’s Municipal Act, 2001, councils can pass fees and charges by-laws for services and activities (e.g., road closures, parks use, right-of-way permits). Many municipalities have updated these by-laws to recover staff costs or apply uniform rules across events. Fair boards then encounter invoices for barricades, police details, or park rentals that used to be in-kind.

2) Safety and regulatory compliance.

Fairs combine animals, food, crowds, vehicles, and often rides. Compliance is non-negotiable, TSSA licences and inspections for amusement devices, electrical and site-safety requirements, and public-health rules for animal exhibits and petting zoos all add time and cost. When municipalities insist on documented compliance, they’re reflecting provincial expectations, not inventing hurdles.

3) Public health and biosecurity.

Ontario health units provide guidance (and sometimes inspections) for animal-contact areas to reduce zoonotic disease risks; organizers are expected to notify their health unit and follow hygiene/traffic-flow protocols. National guidance from Animal Health Canada likewise urges biosecurity plans at exhibitions. These measures are sensible, but they require training and volunteer capacity, both in short supply.

4) Governance modernization.

Agricultural societies are incorporated under the Agricultural and Horticultural Organizations Act. As they update bylaws or navigate the interplay with Ontario’s not-for-profit rules, some municipalities press for clearer documentation (insurance, financials, board policies) as a condition of support. The intent is accountability; the effect can feel like paperwork creep.

Well Cared for Animals

Does tightening support help—or hurt—the community?

The “help” case (as councils see it):

- Uniform fees avoid favouritism and protect taxpayers from subsidizing private activity.

- Clear permits and compliance reduce risk of incidents.

- Cost recovery ensures scarce staff time (traffic control, inspections) isn’t diverted from core services.

The “hurt” case (as communities feel it):

- Abrupt fee schedules and the loss of in-kind services can overwhelm small, volunteer boards, shrinking the fair or pushing it to the brink.

- Dollars not spent at the fairgrounds are dollars not spent at nearby gas bars, cafés, hardware stores, and farm-supply dealers.

- Fairs are part of a public-education mandate that the province itself recognizes through the AHOA’s framework; when local support vanishes, the rural-urban bridge weakens.

The balanced view: scaled, risk-based regulation helps; blanket restrictions and full cost recovery, imposed without transition, usually hurt. Communities pay for that loss in thinner civic life and diminished rural visibility. The history of Ontario fairs shows that when governments and societies collaborate, fairs adapt and thrive; when they’re treated as just another street festival, they wither.

OAAS Logo

A practical partnership model (what “good” looks like)

Communities that get the balance right tend to do five things well:

1) Publish a clear playbook.

A simple “Special Event Manual” spells out timelines, contacts, and every permit the fair will need, from road use to waste and noise. It also lists what the municipality will provide (e.g., traffic barricades, access to power) and what it expects the society to provide (insurance certificates, maps, emergency plan). This makes costs predictable and prevents eleventh-hour surprises. (Municipal fees and road-closure authorities flow from the Municipal Act; codify them and, where justified, codify the waivers too.)

2) Pair compliance with coaching.

- Amusement devices: Coordinate with TSSA and the electrical authority early; host a joint preseason walk-through with your midway provider and municipal staff.

- Animal exhibits: Adopt the health unit’s petting-zoo guidance as standard operating procedure, handwash stations, traffic flow, feed-only zones. Train volunteers.

3) Use multi-year agreements.

One-year approvals exhaust volunteers. Three-year memorandums of understanding (with annual safety reviews) let societies book talent, secure sponsors, and invest in infrastructure.

4) Invest where it multiplies.

A municipality doesn’t need to write big cheques. Small grants for portable wash stations, electrical upgrades, or grandstand repairs pay off for every event held on those grounds. Many societies can also leverage such municipal support when applying for provincial or philanthropic funding.

5) Measure and report.

Track attendance, exhibitor entries, volunteer hours, and vendor counts; gather a few simple economic indicators (hotel bookings, downtown foot traffic). Tie results to municipal objectives, economic development, youth engagement, tourism, cultural heritage, and publish a two-page “Return on Support” summary each fall. (OAAS resources and the AHOA reporting culture make this easier than it sounds.)

Midway

A short, human history lesson (why fairs endure)

The line from 1792 Niagara to a modern arena show ring isn’t straight, but it’s continuous: farmers organizing themselves to improve agriculture and strengthen community; governments recognizing the public value and providing legal frameworks; volunteers doing the heavy lifting. In the 1840s, the provincial fair moved from town to town, drawing crowds and curiosity; by 1879, Toronto locked the idea into a permanent “Ex,” while local societies kept the grassroots model alive. That’s the DNA of Ontario’s fairs, provincial scale, local heart.

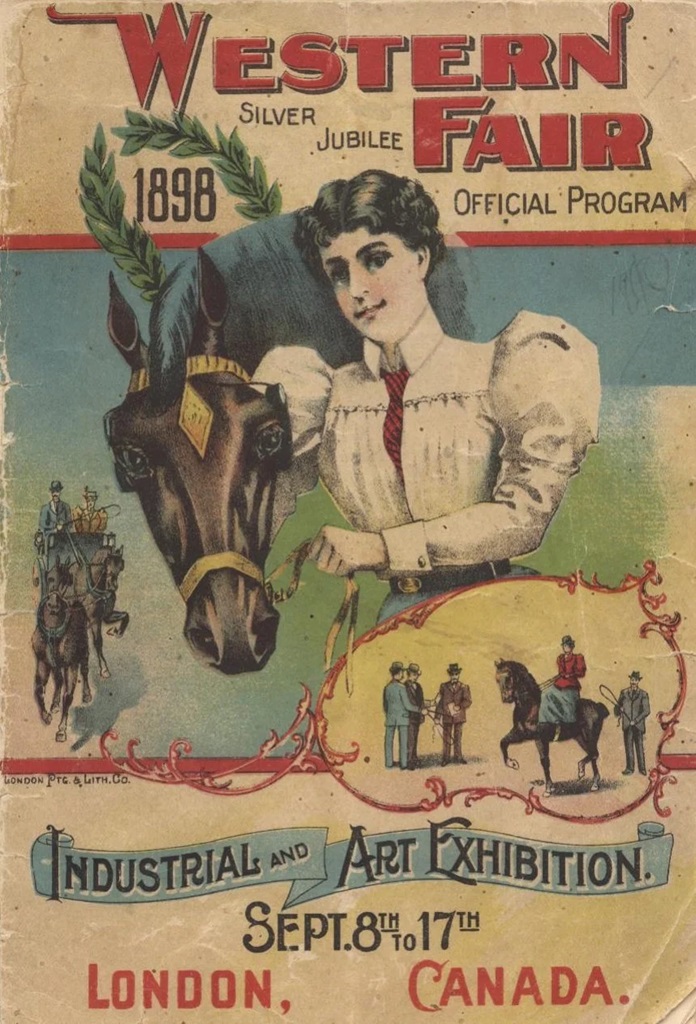

Old Fair Poster

What you can do this year

- Join the society. Memberships are inexpensive; members vote on priorities, volunteer where needed, and keep the institution democratic.

- Adopt a class. Sponsor the junior vegetable tray, the quilting prize, or the 4-H dairy showmanship awards.

- Advance the skills that matter. If you’re a paramedic, electrician, accountant, or event-safety pro, your expertise is worth more than any donation.

- Bring a friend who’s never been. Every new exhibitor begins as a first-time visitor.

- Speak for your fair at council. Ask for a clear, right-sized permit process; predictable event fees; and modest in-kind support tied to measurable outcomes. (Those asks are consistent with provincial law and public-safety expectations.)

Local Society Sign

The bottom line

Agricultural fairs are not an optional extra. They are living civic infrastructure, like libraries, trails, and arenas, built by volunteers and powered by local pride. Rules keep people safe; transparent fees fund municipal services; and modern governance earns public trust. But when those tools are applied without context or collaboration, the damage shows up first in the places that make a town feel like itself.

Ontario has been holding agricultural fairs since the 1800s, and some, like Williamstown, almost since the beginning. They’ve adapted to change before; they can do it again. Give them predictable lanes, a few well-aimed boosts, and a seat at the table, and they’ll keep doing what they’ve always done best: teaching, celebrating, and binding communities together.

Fair Parade